“And, though they never stopped trying, the only words they could make always sounded like the rustling of leaves.”

“And, though they never stopped trying, the only words they could make always sounded like the rustling of leaves.”The thing I am about to tell you might have happened once upon a time. It could have been last week. It makes no difference, the truth is truth no matter when it happens.

In the place where my mother used to live, there were three tongues, each in a different mouth, and of all the tongues that resided in this particular place, these three were the most slithering and maleficent. Not one, but three serpents in the Garden of Eden.

The first tongue belonged to a woman named Helen. Helen was a person who lived on a high moral ground in a great house she richly deserved. She lived alone. Her husband had been a fisherman who fell (some thought dove) from his boat one stormy afternoon and was never seen again. There were three daughters, but each had left to marry, one after the other and all of them lived very far away.

The second tongue belonged to a woman who never married, never gave birth, never so much as cared for a cat because she simply did not have time. Her job, she believed, was to mind the lives of others, and she did so with a ferocity few could circumvent. Her name was Agnes.

The last tongue belonged to a man named Thomas. He also lived alone, unable ever to settle on a wife. Though there were many fine women in the area, none had ever quite suited him. His standards were much too high. Eventually, no one tried anymore to leap the hurdles he had set.

Communities generally have a way of getting along. They mind their own business, or they help when they are able. They offer comfort as needed, a joke, a helping hand, or even silent company when silence is the only thing that will do. In the place where my mother lived all of these things were true. It was also true that there was often anger and resentment that when allowed to fester would erupt in a cataclysm of bitter words and flying fists. Sometimes people broke the law. When that happened there was a price they would have to pay.

What is the price to pay for unrelenting meanness?

In this case, that price began to be tallied up with a wish made by a child. A young boy who delivered eggs to the owners of those sharp tongues. One day, after enduring yet another round of, you clumsy dolt, mind those eggs, and, took you long enough you lazy baboon, and, don’t look at me like that, you rude brat, the boy returned home and wrote: I wish THEY would disappear on a piece of paper. His mother found the paper and asked him what he meant. When he told her she did not scold him. Later, she told her husband what the boy had wished. The next day he told a co-worker about it. The co-worker nodded.

“Yes,” said the co-worker, a man who lived across the street from Helen and had gone to school with Agnes and Thomas. “That is a good wish.”

The co-worker told his wife about the boy’s wish. Three afternoons each week, the man’s wife scrubbed Helen’s kitchen and bathrooms, dusted furniture, and washed windows all while listening to Helen rant. You can’t clean spit, my kitchen is too filthy to use, and if I didn’t follow you around the house, you’d probably rob me blind. I only keep you on because that’s the kind of person I am. Too nice for my own good.

The co-worker’s wife made a wish, too.

When Agnes railed at the woman who cut her hair, I should sue you for incompetence you imbecile, the hairdresser made a wish.

Thomas screamed at a teacher and her fifth-grade class for raking and pulling up weeds in the lot next to his house. You and your brats are getting dirt in my yard. I should have you fired, you’re too stupid to be in charge of kids. Later that day the teacher and her students each went home and made a wish.

For weeks, people wished and wished. Almost always the same wish. I wish THEY would disappear. Except for one. Feeling ashamed of making such a dire wish and being caught out, the little boy who delivered eggs had amended his wish. I wish THEY couldn’t speak he wrote instead. He kept wishing it every day.

Somewhere all those wishes were being tallied. And when there were at last enough of them, something happened.

One morning the sun rose high in the sky over the river that ran through that place. People went about their business not noticing at first, how much lighter the air felt, how warm and inviting the sun was. People smiled and said hello to one another and it wasn’t until a few hours later that they realized the lightness came from the fact that no one had heard the three awful tongues. The bravest in the place went to check. First to Helen’s house. Then to Agnes’s. Finally Thomas’s. No one was there. In fact, it looked as though no one had lived for a very long time at any of those three homes.

But, where three people had vanished from their homes, it also happened that at a lonely spot along the river there suddenly appeared three magnificent trees in a cluster, heads bowed, whispering together as if trying to make sense of how they came to be there.

Let this be fair warning to you: Do not use words to inflict pain. There is no reward waiting — in this world or others — for sharp tongues and wicked minds.

This is not a lesson easily learned.

On the other hand, the trees would be lovely for a long time to come. The town set out picnic tables by the river so that people could sit and watch the water and time drift leisurely past. And where the only sound they heard (besides their own voices) came from the gentle rustle of leaves above them.

The End

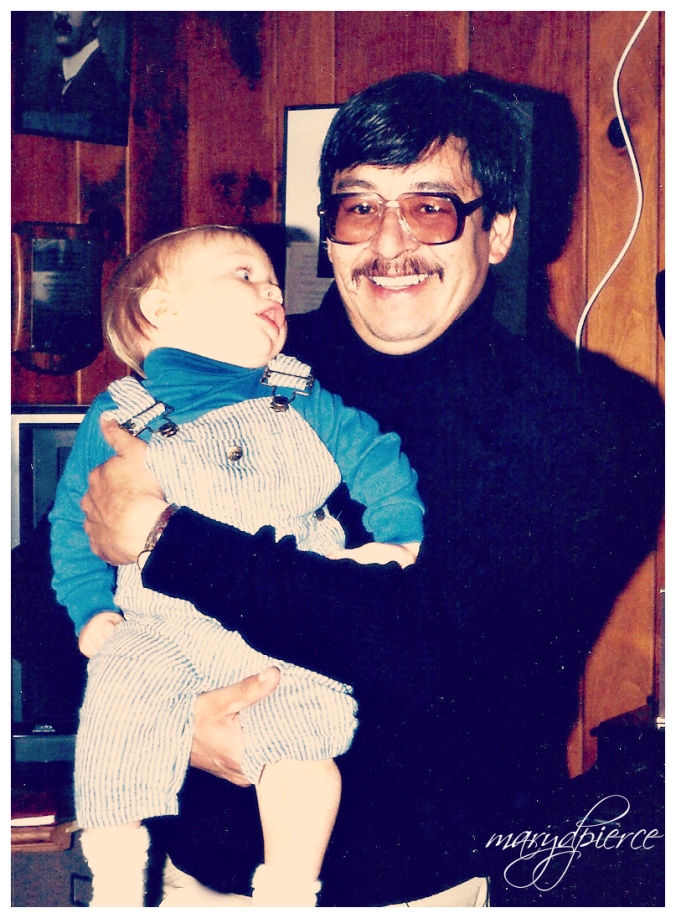

n.b. The photo is a picture of the trees along the St. Lawerence River in Akwesasne where my mother lives. This is the view from her window. I’ve had this photo and the idea that these trees were gossiping mulling around in my brain for awhile. A long time ago my mother told me a story from when she was a little girl living at Akwesasne, about an old woman who was thought to be able to transmute herself at will into a pig. That’s where the idea of transmutation came from. And these days there seem to be so many people speaking such unkind words, I thought a cautionary tale was in order.