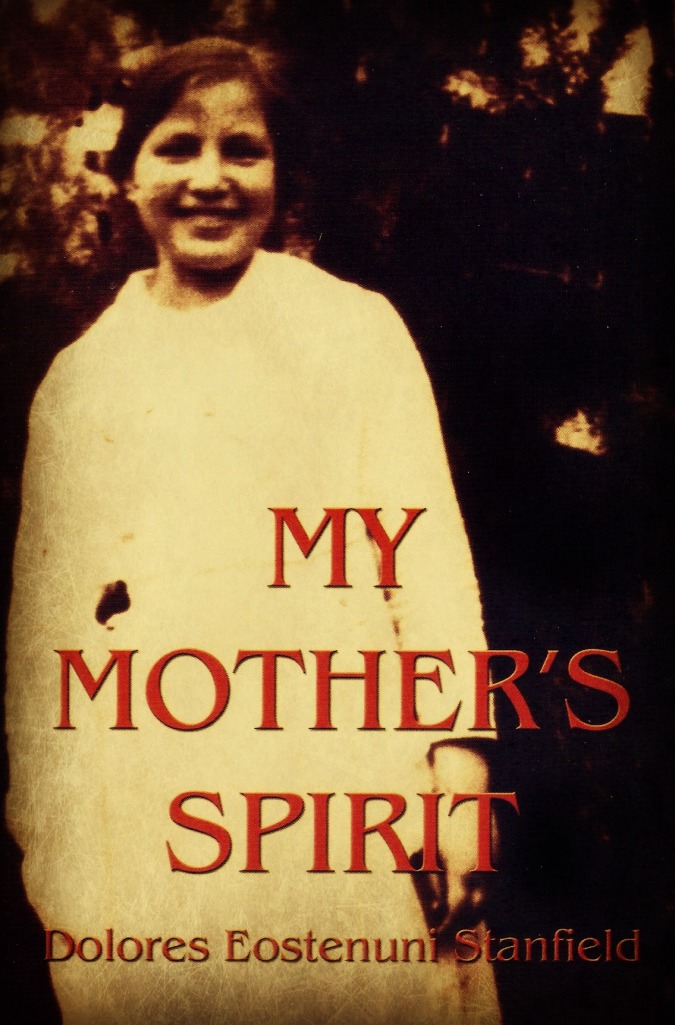

My Mohawk grandmother, Mary Sawatis Jacobs. This is the cover of the book that my mother wrote about growing up on the Mohawk reserve.

My Mohawk grandmother, Mary Sawatis Jacobs. This is the cover of the book that my mother wrote about growing up on the Mohawk reserve.“History is a relentless master. It has no present, only the past rushing into the future. To try to hold fast is to be swept aside.” — John F. Kennedy

When I was a kid, we’d pile into the station wagon and head to the reservation to visit my mother’s Mohawk side of the family. My father liked to go there because the men drank beer, fished, and told stories. My mother liked it, because it was where she felt truly at home. We kids liked to go because we had lots of cousins, the adults got busy talking, and we were left to look after ourselves. In the summer we swam in the river, and traversed the shoreline, weaving through sweetgrass that smelled like fresh rain. The cousins taught us how to swear in Mohawk.

There was one church on the entire reservation and it was Catholic. Father Jacobs was the priest. He was Mohawk, but also a Catholic priest. I never questioned this. The church had a bell tower and a bell rope that hung in the entry. You could pull that rope down and ride half-way to the ceiling when it was time to ring the bell.

Other than hearing the odd word or phrase spoken in the Mohawk language, or the fact that my male cousins all played Lacrosse, there was not a lot to make the reservation seem much different than the town I was from. Except that on the reservation, nothing was paved. There was only dirt and stubby patches of grass. When it rained, people set down planks of wood between their driveway and the door in an effort to keep mud out of the house. Meals were simple, but hearty. The items served most often were corn soup and beef hash. Both of which were lovely and delicious and always homemade. (I guess they also ate a lot of fish, because it was there for the taking, being that the St. Lawrence river wrapped around one side of the reservation, while the St. Regis river cut a swath through the other end. But I don’t like fish so the recollection of it tends be hazy for me.)

What was missing at that time was festival, ritual, and feathers. I don’t remember any Native ceremonies or regalia. There were no sweat lodges. No pow wows. No moccasin-ed dancing for rain or peace or any other thing. If we attended church there, it was the same Catholic mass as the one we experienced at home.

The point is, that my comprehension then of what it was like to be Mohawk, to be a Native American living on a reservation, was lacking cultural context. It was years before I understood why. I knew that when my mother was growing up, many of her cousins were taken from their homes and placed in an Industrial boarding school in Canada. They were forbidden to speak their native language or participate in native ceremony. They were there, boys and girls (in separate schools), to be “educated”, which actually meant, to learn to be “white.”

That those schools were often brutal, the quality of education poor, and the food even worse, is well documented. But Indian schools did more than decimate native cultures, they robbed those children of any value they previously may have thought they had.

Without a culture or a sense of worth, what is left?

My mother’s reservation has come back to their culture slowly, like a long forgotten memory drifting into consciousness once again. It is not called St. Regis anymore. We use the Mohawk word instead, Akwesasne. I love the sound of that.

I began this post on Monday, which was Columbus Day. In part because of the Daily Post Weekly Writing Challenge, which had as a topic: Living History. But mostly because of the day, which my mother cannot let go by without muttering at least once — Columbus, that murdering bastard!

And then I read a piece in the Washington Post which made me wonder again, why do we keep a holiday in honor of a man we now know dealt a brutal hand against the natives of the lands he explored (which wasn’t even America)? In one of the reader comments, a man asked if there actually were any Indian reservations around these days? I was about to reply that why, yes, in fact there were many reservations still around, but then I spied another comment a few lines down that wisely pointed out – Do not feed the trolls. And I realized, of course, it does no good. You can lead a person to information, but you cannot make them think.

Still. Can we agree to not honor mean men? I’d like to believe that history can teach us how to live better. Kinder.

Maybe one day, we could even get it right.

n.b. The title of this post is a quote taken from a paper read at a convention in 1892 by Richard Henry Pratt, the U.S. Army officer whose brainchild it was to assimilate Indians into a white society.