This is not an ordinary Christmas tree. This tree (though you may not be able to tell at first glance) is perfect. It is our tree, the one that grew to just the right size and then waited for us to find it. Every year there is one and only one tree for us, and we always find it, we always do. And it is perfect. Every year.

This is not an ordinary Christmas tree. This tree (though you may not be able to tell at first glance) is perfect. It is our tree, the one that grew to just the right size and then waited for us to find it. Every year there is one and only one tree for us, and we always find it, we always do. And it is perfect. Every year.

See those little red bows, like the notes of a perfect song, scattered over the branches? Those bows are from our first Christmas spent in this house, which was newly built with purpose and unfailing energy, and mostly by our own hands. I made those bows from a fat spool of ribbon and some gold thread that I bought at the Christmas Tree Shops for practically nothing, because we had so little money that year (the house had eaten most of what we had). And though, they’re hard to pick out in the photo, there are the wicker ornaments, swirled in strands of red and green thread, that we got on our belated Mexican honeymoon just weeks before.

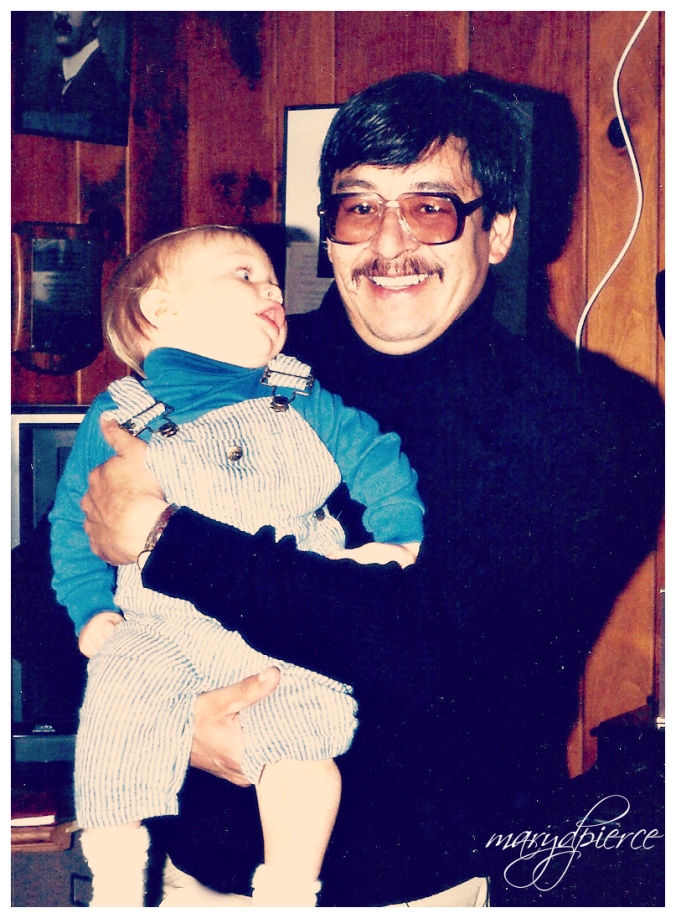

Our life together hangs on that tree. The Boy’s first dough ornaments; the clay ornaments I made; favorite friends Pikachu and Woody (who still swings his lariat from one of the branches); tiny lockets that hold our Boy’s sweet face with forever smiles at ages two, and five, and seven. The places we’ve been and the things we’ve seen. All of them carried home to remember the fun: The Pinocchio and nutcrackers with movable legs; the crowns and the stars and the snowy white owl; a streetcar emblazoned with the year we saw San Francisco. A clown on a unicycle found in a shop that we’d stepped into to escape the frigid Montreal air.

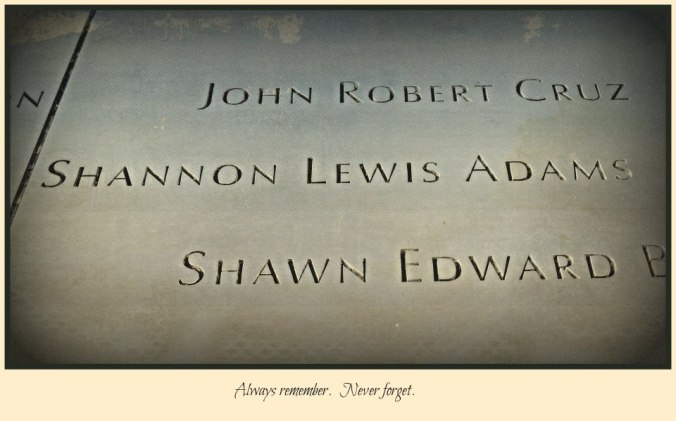

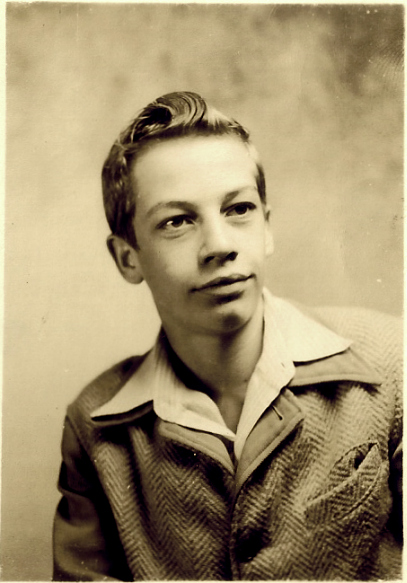

Our family and our friends, the ones still living, and those who have gone, are there. In ornaments hand made and store bought, given in love and accepted with gratitude.

Our tree is perfect because it reminds us of what we have and what we’ve shared. When the Boy was small, the bedtime ritual once the tree went up, was to turn off all the lights, save the ones on the tree, and then the three of us sat together and admired the tree. My husband and I still do this some nights, though the Boy is gone to a place of his own. We sit sometimes, in the glow of the lights, nostalgic as parents of grown children often are. And, even in that there is perfection.

We are blessed.

May you all be, as well.